Unstoppable code

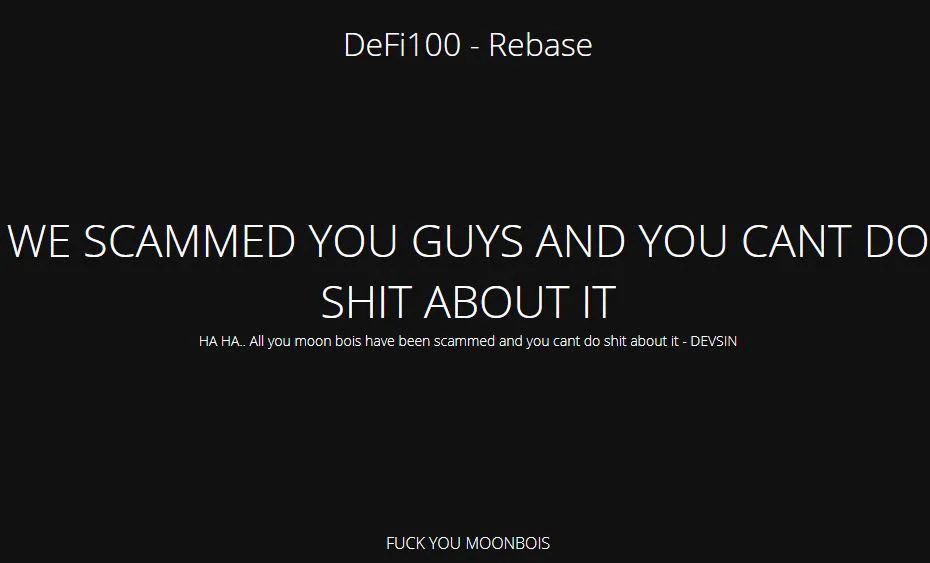

This is the website of DeFi100, a "decentralized finance" system running on the Binance Smart Chain, after the promoters pulled a $32M exit scam. Their message sums up the ethos of cryptocurrencies:

The business model of crypto is to provide a platform for crooks to scam muppets without running the risk of jail time. Few understand this. https://t.co/vFeyosRKPE

— Trolly🧻 McTrollface 🌷🥀💩 (@Tr0llyTr0llFace) May 7, 2021

Governments around the world have started to wake up to the fact that this message isn't just for the "muppets", it is also the message of cryptocurrencies for governments and civil society. Below the fold I look into how governments might respond.

The externalities of cryptocurrencies include:

- Massive carbon emissions.

- Funding "rogue states" such as North Korea and Iran.

- Tax evasion.

- Laundering the proceeds of crime, including the drug trade, theft and fraud, and armed robbery.

- An epidemic of ransomware.

- A wave of securities fraud targeting the greedy and vulnerable.

- Shortages of products including graphics cards, hard disks, and chips in general as limited fab capacity is diverted to mining ASICS.

- Abuse of free tiers of Web services.

- Noise pollution.

It seems that recent ransomware attacks, including the May 7th one on Colonial Pipeline and the less publicized May 1st one on Scripps Health La Jolla, have reached a tipping point. Kat Jerick's Scripps Health slowly coming back online, 3 weeks after attack reports:

"It’s likely that it’s taking a long time because of negotiations going on with the perpetrators, and the prevailing narrative is that they have the contents of the electronic health records system that are being used for 'double extortion,'" said Michael Hamilton, former chief information security officer for the city of Seattle and CISO of healthcare cybersecurity firm CI Security, in an email to Healthcare IT News.

If that's true, Scripps certainly wouldn't be alone: The healthcare industry saw a number of high-profile ransomware incidents in the last year, including a cyberattack on Universal Health Services that led to a lengthy network shutdown and a $67 million loss.

More recently, customers of the electronic health record vendor Aprima also reported weeks of security-related outages.

In response governments are trying to regulate (US) or ban (China, India) cryptocurrencies. The libertarians who designed the technology believed they had made governments irrelevant. For example, the Decentralized Autonomous Organization (DAO)'s home page said:

The DAO's Mission: To blaze a new path in business organization for the betterment of its members, existing simultaneously nowhere and everywhere and operating solely with the steadfast iron will of unstoppable code.

This was before a combination of vulnerabilities in the underlying code was used to steal its entire contents, about 10% of all the Ether in circulation.

If cryptocurrencies are based on the "iron will of unstoppable code" how would regulation or bans work?

Nicholas Weaver explains how his group stopped the plague of Viagra spam in The Ransomware Problem Is a Bitcoin Problem:

Although they drop-shipped products from international locations, they still needed to process credit card payments, and at the time almost all the gangs used just three banks. This revelation, which was highlighted in a New York Times story, resulted in the closure of the gangs’ bank accounts within days of the story. This was the beginning of the end for the spam Viagra industry. ... Subsequently, any spammer who dared use the “Viagra” trademark would quickly find their ability to accept credit cards irrevocably compromised as someone would perform a test purchase to find the receiving bank and then Pfizer would send the receiving bank a nastygram.

Weaver draws the analogy with cryptocurrencies and "big-game" ransomware:

These operations target companies instead of individuals, in an attempt to extort millions rather than hundreds of dollars at a time. The revenues are large enough that some gangs can even specialize and develop zero-day vulnerabilities for specialized software. Even the cryptocurrency community has noted that ransomware is a Bitcoin problem. Multimillion-dollar ransoms, paid in Bitcoin, now seem to be commonplace.

This strongly suggests that the best way to deal with this new era of big-game ransomware will involve not just securing computer systems (after all, you can’t patch against a zero-day vulnerability) or prosecuting (since Russia clearly doesn’t care to either extradite or prosecute these criminals). It will also require disrupting the one payment channel capable of moving millions at a time outside of money laundering laws: Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. ... There are only three existing mechanisms capable of transferring a $5 million ransom — a bank-to-bank transfer, cash or cryptocurrencies. No other mechanisms currently exist that can meet the requirements of transferring millions of dollars at a time.

The ransomware gangs can’t use normal banking. Even the most blatantly corrupt bank would consider processing ransomware payments as an existential risk. My group and I noticed this with the Viagra spammers: The spammers’ banks had a choice to either unbank the bad guys or be cut off from the financial system. The same would apply if ransomware tried to use wire transfers.

Cash is similarly a nonstarter. A $5 million ransom is 110 pounds (50 kilograms) in $100 bills, or two full-weight suitcases. Arranging such a transfer, to an extortionist operating outside the U.S., is clearly infeasible just from a physical standpoint. The ransomware purveyors need transfers that don’t require physical presence and a hundred pounds of stuff.

This means that cryptocurrencies are the only tool left for ransomware purveyors. So, if governments take meaningful action against Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, they should be able to disrupt this new ransomware plague and then eradicate it, as was seen with the spam Viagra industry.

For in the end, we don’t have a ransomware problem, we have a Bitcoin problem.

I agree with Weaver that disrupting the ransomware payment channel is an essential part of a solution to the ransomware problem. It would require denying cryptocurrency exchanges access to the banking system, and global agreement to do this would be hard. Given the involvement of major financial institutions and politicians, it would be hard even in the US. So what else could be done?

Nearly a year ago Joe Kelly wrote a two-part post explaining how governments could take action against Bitcoin (and by extension any Proof-of-Work blockchain). In the first part, How To Kill Bitcoin (Part 1): Is Bitcoin ‘Unstoppable code’? he summarized the crypto-bro's argument:

They say Bitcoin can’t be stopped. Just like there’s no way you can stop two people sending encrypted messages to each other, so — they say — there’s no way you can stop the Bitcoin network.

There’s no CEO to put on trial, no central server to seize, and no organisation to put pressure on. The Bitcoin network is, fundamentally, just people sending messages to each other, peer to peer, and if you knock out 1 node on the network, or even 1,000 nodes, the honey badger don’t give a shit: the other 10,000+ nodes keep going like nothing happened, and more nodes can come online at any time, anywhere in the world.

So there you have it: it’s thousands of people running nodes — running code — and it’s unstoppable… therefore Bitcoin is unstoppable code; Q.E.D.; case closed; no further questions Your Honour. This money is above the law, and governments cannot possibly hope to control it, right?

The problem with this, as with most of the crypto-bros arguments, is that it applies to the Platonic ideal of the decentralized blockchain. In the real world economies of scale mean things aren't quite like the ideal, as Kelly explains:

It’s not just a network, it’s money. The whole system is held together by a core structure of economic incentives which critically depends on Bitcoin’s value and its ability to function for people as money. You can attack this.

It’s not just code, it’s physical. Proof-of-work mining is a real-world process and, thanks to free-market forces and economies of scale, it results in large, easy-to-find operations with significant energy footprints and no defence. You can attack these.

If you can exploit the practical reality of the system and find a way to reduce it to a state of total economic dysfunction, then it doesn’t matter how resilient the underlying peer-to-peer network is, the end result is the same — you have killed Bitcoin.

Kelly explains why the idea of regulating cryptocurrencies is doomed to failure:

The entire point of Bitcoin is to neutralise government controls on money, which includes AML and taxes. Notice that there’s no great technological difficulty in allowing for the completely unrestricted anonymous sending of a fixed-supply money — the barrier is legal and societal, because of the practical consequences of doing that.

So the cooperation of the crypto world with the law is a temporary arrangement, and it’s not an honest handshake. The right hand (truthfully) expresses “We will do everything we can to comply” while the left hand is hard at work on the technology which makes that compliance impossible. Sure, Bitcoin is pretty traceable now, and sometimes it even helps with finding criminals who don’t have the technical savvy to cover their tracks, but you’ll be fighting a losing battle over time as stronger, more convenient privacy tooling gets added to the Bitcoin protocol and the wider ecosystem around it. ... So yeah: half measures like AML and censorship aren’t going to cut it. If you want to kill Bitcoin, that means taking it out wholesale; it means forcing the system into disequilibrium and inducing economic collapse.

In How To Kill Bitcoin (Part 2): No Can Spend Kelly explains how a group of major governments could seize control of the majority of the mining power and mount a specific kind of 51% attack. The basic idea is that governments ban businesses, including exchanges, from transacting in Bitcoin, and seize 80% of the hash rate to mine empty blocks:

As it stands, after seizing 80% of the active hash rate, you can generate proof-of-work hashes at 4x the speed of the remaining miners around the world.

- You control ~80 exahashes/sec, they control ~20 exahashes/sec

- For every valid block that rebel miners, collectively, can produce on the Bitcoin blockchain, you can produce 4

... You use your limitless advantage to execute the following strategy:

- Mine an empty block — i.e. a block which is perfectly valid but contains no transactions

- Keep 5–10 unannounced blocks to yourself — i.e. mine 5–10 ‘extra’ empty blocks ahead of where the chain tip is now, but don’t actually share any of these blocks with the network

- Whenever a rebel miner announces a valid block, orphan it (override it) by announcing a longer chain with more cumulative proof-of-work — i.e. announce 2 of your blocks

- Repeat (go back to 2)

The result of this is that Bitcoin transactions are no longer being processed, and you’ve created a black hole of expenditure for rebel miners.

- Every time a rebel miner spends $ to mine a block, it’s money down the drain: they don’t earn any block rewards for it

- All transactions just sit in the mempool, being (unstoppably) messaged back and forth between nodes, waiting to be included in a block, but they never make it in

In other words, no-one can spend their bitcoin, no matter who they are or where they are in the world.

Empty blocks wouldn't be hard to detect and ignore, but it would be easy for the government miners to fill their blocks with valid transactions between addresses that they control.

Things have changed since Kelly wrote, in ways that complicate his solution. When he wrote, it was estimated that 75% of the Bitcoin mining power was located in China; China could have implemented Kelly's attack unilaterally. But since then China has been gradually increasing the pressure on cryptocurrency miners. This has motivated new mining capacity to set up elsewhere. The graph shows a recent estimate, with only 65% in China. As David Gerard reports:

Bitcoin mining in China is confirmed to be shutting down — miners are trying to move containers full of mining rigs out of the country as quickly as possible. It’s still not clear where they can quickly put a medium-sized country’s worth of electricity usage. [Reuters] ... Here’s a Twitter thread about the miners getting out of China before the hammer falls. You’ll be pleased to hear that this is actually good news for Bitcoin. [Twitter]

If the recent estimate is correct, Kelly's assumption that a group of governments could seize 80% of the mining power looks implausible. The best that could be done would be an unlikely agreement between the US and China for 72%. So for now lets assume that the Chinese government is doing this alone with only 2/3 of the mining power. Because mining is a random process, they are thus only able on average to mine 2 blocks for every one from the "rebel" miners.

Because Bitcoin users would know the blockchain was under attack, they would need to wait several blocks (the advice is 6) before regarding a transaction as final. The rebels would have to win six times in a row, with probability 0.14%, for a transaction to go through. The Bitcoin network can normally sustain a transaction rate of around 15K/hr. Waiting 6 block times would reduce this to about 20/hr. Even if the requirement was only to wait 3 block times, the rate would be degraded to about 550/hr, so the attack would greatly reduce the supply of transactions and greatly increase their price.

The recent cryptocurrency price crash caused average transaction fees to spike to about $60. In the event of an attack like this HODL-ers would be desperate to sell their Bitcoin, so bidding for the very limited supply of transactions would be intense. Anyone on the buy-side of these transactions would be making a huge bet that the attack would fail, so the "price" of Bitcoin in fiat currencies would collapse. Thus the economics for the rebel miners would look bleak. Their chances of winning a block reward would be greatly reduced, and the value of any reward they did win would be greatly reduced. There would be little incentive for the rebels to continue spending power to mine doomed blocks, so the cost of the attack for the government would drop rapidly once in place.

The cost of the attack is roughly 2/3 of 6.25 BTC/block times 144block/day. Even making the implausible assumption that the price didn't collapse from its current $35K/BTC the cost is $21M/day or $7.6B/yr. A drop in the bucket for a major government. Thus it appears that, until the concentration of mining power in China decreases further, the Chinese government could kill Bitcoin using Kelly's attack. For an analysis of an alternate attack on the Bitcoin blockchain see In The Economic Limits of Bitcoin and the Blockchain by Eric Budish.

Kelly addresses the government attacker:

Normally what keeps the core structure of incentives in balance in the Bitcoin system, and the reason why miners famously can’t dictate changes to the protocol, or collude to double-spend their coins at will, is the fact that for-profit miners have a stake in Bitcoin’s future, so they have a very strong disincentive towards using their power to attack the network.

In other words, for-profit miners are heavily invested in and very much care about the future value of bitcoin, because their revenue and the value of their mining equipment critically depends on it. If they attack the network and undermine the integrity of Bitcoin and its fundamental value proposition to end users, they’re shooting themselves in the foot.

You don’t have this problem.

In fact this critical variable is flipped on its head: you have a stake in the destruction of Bitcoin’s future. You are trying to get the price of BTC to $0, and the value of all future block rewards along with it. Attacking the network to undermine the integrity of Bitcoin and its value proposition to end users is precisely your goal.

This fundamentally breaks the game theory and the balance of power in the system, and the result is disequilibrium.

In short, Bitcoin is based on a Mexican Standoff security model which only works as a piece of economic design if you start from the assumption that every actor is rational and has a stake in the system continuing to function.

That is not a safe assumption.

There are two further problems. First, Bitcoin is only one, albeit the most important, of almost 10,000 cryptocurrencies. Second, some of these other cryptocurrencies don't use Proof-of-Work. Ethereum, the second most important cryptocurrency, after nearly seven years work, is promising shortly to transition from Proof-of-Work to Proof-of-Stake. The resources needed to perform a 51% attack on a Proof-of-Stake blockchain are not physical, and thus are not subject to seizure in the way Kelly assumes. I have written before on possible attacks in Economic Limits Of Proof-of-Stake Blockchains, but only in the context of double-spending attacks. I plan to do a follow-up post discussing sabotage attacks on Proof-of-Stake blockchains once I've caught up with the literature